Tour de France: a well-oiled (economic) machine

The Tour de France's business model underwent profound changes in the 1980s and 1990s, and today it still draws on much of the same model.

The Tour de France 2023 set off from Bilbao, in Spain's Basque country, on Saturday, July 1st. Many of the 176 riders dreamed of crossing the finish line on the Champs-Élysées on Sunday, July 23rd, wearing the yellow jersey and adding their name to the list of winners. A tough battle is expected between Slovenia's Tadej Pogačar and Denmark's Jonas Vingegaard, the last two winners of the race (and also the last two runners-up). The former, before injuring his wrist, won this year's Paris-Nice, Tour of Flanders and Flèche wallonne (among others); the latter had no rival on the critérium du Dauphiné Libéré in June. Egan Bernal (winner in 2019), Jai Hindley (winner of last year's Giro d'Italia) and Frenchmen David Gaudu and Romain Bardet will be among those trying to catch up with their wheels (and why not outrun them).

In addition to the glory of having their name inscribed on the prize list, the overall leader will also pocket a 500,000 euro bonus (to be shared with his seven team-mates). 200,000 euros are reserved for the runner-up, and 100,000 for the third. Bonuses decrease in this way up to 20th place. The bonus is then the same until 160th place, at 1,000 euros. These sums have changed little since the early 2000s. The winner's team pocketed 400,000 euros in 2003, 450,000 in 2006 and 500,000 from 2016 onwards.

In fact, it was mostly in the 1980s and 1990s that the Tour de France saw its main changes. When working on my History of the Tour de France, it was admittedly rather difficult to sketch out its economic history, as Amaury Sport Organisation, the event's organizer, does not publish its accounts. Nevertheless, enough sources testify to a profound transformation in the economy of the Grand Loop during those two decades, and today it still draws on much of the same model.

Booming Broadcasting Rights

According to many sources, the Tour did not start to become profitable until the second half of the 1970s. At that time, it made annual profits of around 1,500,000 francs on sales of around 10,000,000 francs. In the early 1960s and early 1970s, annual losses were estimated at 200,000 F on sales of around 4,000,000.

The latter had been on an upward trajectory since the Liberation after WWII, but literally exploded in the 1980s and 1990s. In two decades, it rose from 5 to 50 million euros. A large part of this increase—around a third—is linked to the rise in television broadcasting rights, which increased 65-fold over this period. All this made it possible to professionalize the organization and create, for example, the Start Village and its events in 1988.

One reason for this is the changing structure of the market for broadcasting rights. Before the 1980s, on the demand side, television channels were all public and did not compete with each other. On the supply side, on the other hand, sports event organizers are already relatively numerous in their desire to give visibility to their competitions. They need it, not least because their sponsorship and advertising revenues also depend on it. This gives broadcasters considerable negotiating power.

However, the landscape changed dramatically in the 1980s. The first private channel, Canal+, was launched in 1984, and M6 began broadcasting in 1987, the year TF1 was privatized... To broadcast the Grande Boucle, the channels had to win a bidding process.

Revenues from sponsorship and advertising also increased in this wake, but at a much slower rate. Representing two-thirds of revenues at the end of the 1980s, their share of sales was overtaken by broadcasting rights in the early 2000s. Event director Jean-Marie Leblanc took advantage of this situation to reduce the number of sponsors in the 1990s. From ten or so, they were reduced to four main sponsors, one for each distinctive jersey. Since then, Crédit Lyonnais (LCL since 2006) has been the sole sponsor of the yellow jersey. This choice was not without interest for the spectacle, notably reducing the length of the protocol ceremonies.

Stopover towns (where the racers stay the night) even if their contributions continued to grow, have seen the weighting in total revenues fall, from 40% in 1952 to 5% in 2003.

Bonuses Calibrated for Spectacle

As sales have grown, so have the bonuses and rewards awarded to the peloton, in order to continue attracting the best cyclists. In 1980, the average rider earned 2.6 months of the average French salary in bonuses; by 2000, this had risen to almost eight months. Over the 1980s and 1990s, the bonuses associated with the Tour increased in constant currency by a factor of around 3.5 for the average rider, and by a factor of ten for the winner. In 1980, the latter earned eight times more than the average rider, and twenty-five times more in 2000.

This difference can be explained by the economic theory of tournaments. This theory teaches that the incentive for participants in a sporting event to spend all their energy on winning does not depend so much on the prize money as on the difference in prize money between first and second place, second and third place and so on. This would also account for the reduction in performance deltas between the very best riders. Bonuses are shared within each team, to also reward the efforts made by teammates to put their leader in the best possible conditions on the road.

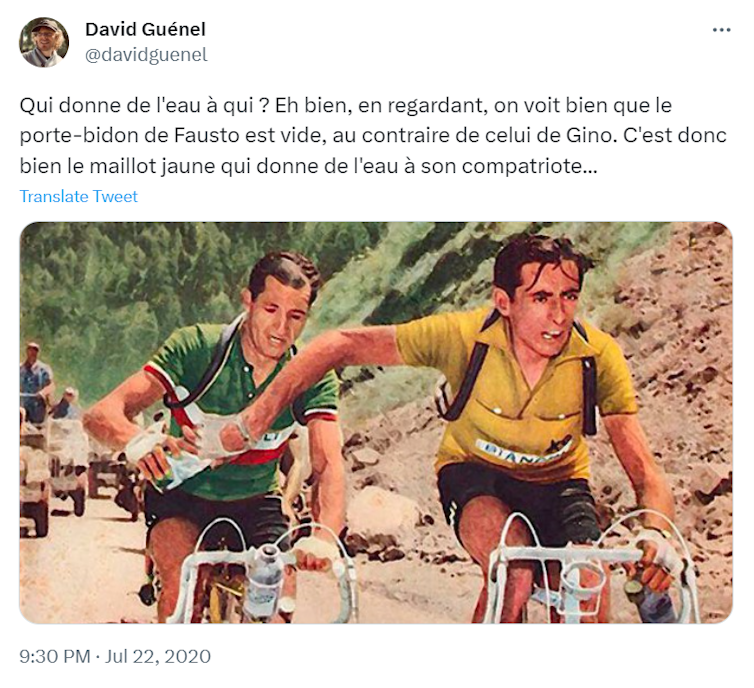

Of course, the desire to win the Tour exists independently of a monetary bonus. On the part of the organizers, however, the structure of the bonuses has probably always been designed to motivate the riders to fight, rather than to enable them to divide up the money with less effort. In 1952, for example, when Fausto Coppi crushed the race after the Alpe d'Huez and Sestriere stages (10th and 11th out of 23), the race directors, fearing that the rest of the field would give up and the race would lose interest, doubled the bonuses for second and third place.

Who is giving water to whom? Well, looking closer, one can clearly see that Fausto's water bottle is empty, and Gino’s is not. So it’s actually the yellow jersey (race leader) who is giving water to his compatriot.

In this way, they aim to put on a show, if not for first place, then at least for the subsequent ones. More unexpectedly, to motivate riders to fight, some race organizers have sometimes ousted riders: while in 1929 Alfredo Binda won the Giro d'Italia for the fourth time, in 1930 the Giro organizers paid him a sum equivalent to the first prize so that he wouldn't take part in the race!

Riders' remuneration from bonuses must be distinguished from their fixed salaries, paid by teams whose name is that of a sponsor. Its evolution can be explained by the "superstar economy" model: sponsors are prepared to pay more and more for the services of the small number of riders who guarantee increasing media exposure.

An evolution specific to cycling?

Sales multiplied by a factor of 10, TV broadcasting rights by a factor of around sixty-five—rapid though the Tour's growth was in the 1980s and 1990s, it was nevertheless much slower than that of soccer. Over the same period, in France, sales of professional soccer clubs increased by a factor of around twenty and television rights to soccer matches by a factor of around three hundred.

Competition from television channels has been a far more powerful catalyst for football. Compared to cycling, soccer is an ideal sport for television broadcasting. It's easier to capture because it takes place in a stadium, rather than on a course sometimes over 200 kilometers long. It's also easier to program, since the duration of the matches is known, unlike a stage, which is more unpredictable. As a result, the Tour has not benefited as much as French soccer clubs from the considerable increase in the volume of investment in sport that characterized the 1980s and 1990s.

However, it did benefit more than the Olympic Games worldwide. On the one hand, this can be explained by the fact that the liberalization of the television market, the main factor behind the explosion in sales, took place earlier, later or not at all in other Western countries. Secondly, most of the world's inhabitants are significantly less wealthy than the French, and advertising is therefore less valuable to advertisers.

Jean-François Mignot, Demographer, Sorbonne University

This article has been translated and republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons licence. Click here to read the original publication, article in French.

![]()