Discovering the Institut de papyrologie

In the heart of Paris' 16th arrondissement, within the Inspé, lies a hidden treasure: the Institut de papyrologie.

Attached to the Greek department, it houses Sorbonne University's papyrus and cartonnage collection, one of the largest in France. In this report, we take you on a journey of discovery of this unique place and the people who preserve it.

Custodians of the collection, papyrologist and associate professor Benoît Laudenbach, and papyrothécaire Florent Jacques, welcome us to rue Molitor, where the Institut de papyrologie (available only in French) took up residence following the completion of the Sorbonne campus in 2010.

Benoit Laudenbach et Florent Jacques

Behind them, in a room of the papyrology library, stands the bust of the Institute's founding father, French papyrologist Pierre Jouguet. This papyrologist established the collection in the 1920s, first in a parlour at Collège Sainte-Barbe and later at the Sorbonne, by collecting papyri and cartonnage from purchases and archaeological digs. Thanks to him, Sorbonne University is the only French university to own and preserve a papyrus collection of this magnitude, on which researchers continue to work and students to train.

A collection that is unique in the world

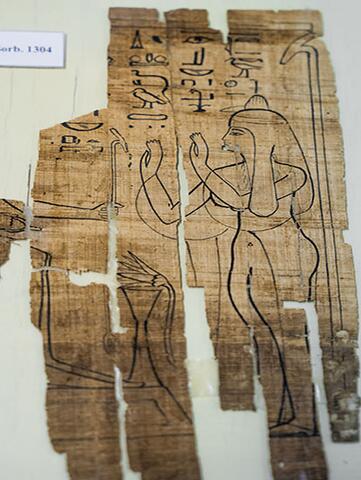

To discover the collection, you have to wander through a maze of underground corridors reminiscent of the subterranean labyrinths of the pyramids. Pierre Jouguet's 19th-century explorations of the Ptolemaic necropolises of the Fayoum brought back some unique artifacts: cartonnages of death masks found on mummies dating from the end of the Pharaonic era (between 300 and 100 BC). These pieces, sometimes decorated with gold leaf, were made from recycled papyrus mixed with white stucco, forming a kind of papier-mâché. While some of the cartonnages were dismantled to recover the papyrus of which they were composed, others were preserved and restored for their pictorial and museographic interest. "In this case, the interest of the object takes precedence over that of any texts that might have been found. It's always a moral question to sacrifice one object in order to discover another," explains Benoît Laudenbach.

Masque de momie doré (Inv.Sorb. 2766) en cartonnage à base de papyrus

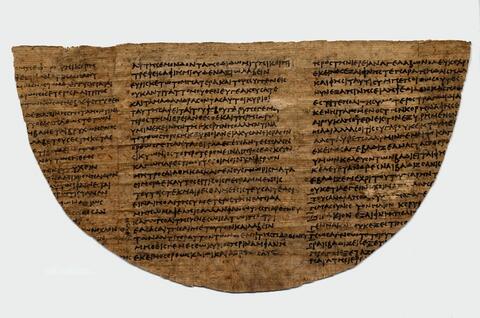

Among the hundreds of papyri in the boxes, there is a plan for the irrigation of agricultural plots dating from the 3rd century BC, a down payment for a contract for the hire of a donkey, a complaint against a village chief for slanderous denunciation, and even the largest papyrus documentary book in the world: a 132-page tax codex divided into two volumes. This exceptional work has made it possible to reconstruct the tax system of an Egyptian region called Hermopolite, providing historians with invaluable sociological information. This Prévert-like inventory plunges us into the daily life of the Egyptians of the time.

Devis de travaux avec plan pour l’irrigation du domaine d’Apollônios (Inv.Sorb. 1) ©Sorbonne Université

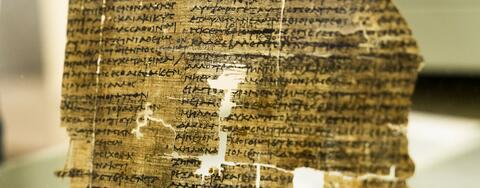

The centerpiece of the collection is a fragment of a papyrus scroll dating from the 3rd century BC, the earliest evidence of an edition of Homer's Odyssey. By revealing variants of the famous passage on the Cyclops, it offers an insight into the evolution of the Homeric text before its stabilization.

Le passage célèbre du Cyclope sur le plus vieux rouleau de papyrus de l’Odyssée d’Homère (Inv.Sorb. 2245) ©Sorbonne Université

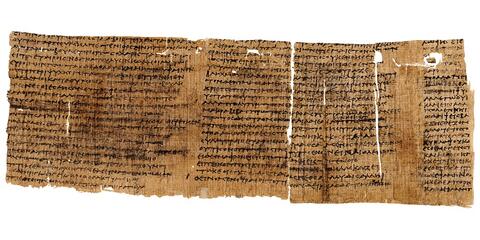

Other discoveries include a play by Menander, a famous author of comedy from Antiquity who fell into oblivion in the Middle Ages, on the back of a cardboard breastplate. Although reconstructing the text was an arduous task, around two-thirds of the play is now available for publication.

Fragment de la pièce Les Sicyoniens de Ménandre réutilisé pour un plastron en cartonnage ©Sorbonne Université

In addition to the papyri collected by Pierre Jouguet, the Institut de papyrologie holds the collections of two other papyrologists. Although the Urbain Bouriant collection, Jouguet's former teacher, has yet to be studied, it includes a number of curiosities, such as a pedagogical method for learning to read Greek, and a defixion tablet, i.e. a request to curse the powers of the underworld.

Une méthode pédagogique de lecture en grec sous forme d’un petit cahier (P.Bour. 1) ; une tablette de défixion sur plomb (P.Rein. II 88) ©Sorbonne Université

The Théodore Banach Reinach collection, bequeathed to the Institut after the death of this generous patron in 1928, includes rare calcined papyri from the Nile delta, whose ink is still discernible.

Fragment de rouleau calciné de registre d’arriérés d’impôts du nom de Mendès (P.Thmouis) ©Sorbonne Université

The restauration work

To keep these fragile treasures in good condition, papyro-archaeologist Florent Jacques carries out restoration work. In a cramped room on the second floor, we discover a small laboratory equipped with a scanner, a photo-agglomerator and a glass-covered bench. On the wall, a few coins, protective foams and chemicals are stored on shelves. "Restoring a papyrus has a triple objective," explains Florent Jacques: to prevent it from deteriorating over time, to reconstitute the document as completely as possible for editing and translation, and finally to make it legible for researchers. I perform basic operations adapted to the Sorbonne University collection. I consolidate the pieces, clean them and pack them under glass or in suitable boxes. And when a papyrus is folded, it needs to be moistened to soften it before being reshaped with spatulas and left to dry under a press for two days."

Intérieur d’un masque de momie, conservé dans un cadre enserré dans une mousse spéciale. ©Sorbonne Université

In the papyrothécaire's lair, we can see a cartonnage mask of a Ptolemaic mummy, on the back of which we discover texts in Demotic, a variant of Egyptian. It is one of the forty or so pieces selected for the exhibition scheduled for May 2024 in Bordeaux, devoted to Jouguet's cartonnage.

Indeed, the Institut de Papyrologie is committed to sharing the richness of its collection with the general public. To this end, Florent Jacques and Benoît Laudenbach regularly take part in exhibitions in France and abroad, organize a dozen guided tours a year, particularly for students and schoolchildren, and sometimes open the doors to the collection on Heritage Days. They have also made part of the collection available online in the form of high-resolution photos, facilitating research for students and researchers from all over the world. They will shortly be launching a 3D digitization project of the cartonnages with a team from Sorbonne University. As for the library housing papyrology journals and publications, it is open to all, from researchers to the simply curious. "One day, a novelist even came to research mummy masks for his novel," recounts Florent Jacques.

Research at work

"As academics, we may exhibit fewer objects than a museum, but we can easily take out a papyrus to work on it, analyze the ink, for example," explains Benoit Laudenbach. This research work is carried out in particular during the papyrology seminars, which bring together a dozen students and researchers every Wednesday in the midst of magazines and papyri. Together, they work on deciphering texts often written in Greek, sometimes Latin, hieroglyphics, hieratic Egyptian, Demotic, Coptic or Arabic.

Deciphering the texts is like a real investigation. "We look, for example, at the spelling of a word in order to date it, but also at where it was produced," explains the papyrologist. The material of the document also provides many clues. Is it a single sheet, a recycled papyrus? Is it from a scroll or a book? Researchers are also beginning to rely on analyses of ink composition to date the document, as certain mixtures appeared at very specific moments in history. "My best reconstructions are those I've made on fragments written in languages I didn't master," confides the papyrothesist. One day, I was working with a renowned papyrologist on the reconstruction of a fragment in Demotic. It was a real puzzle. And, even though I didn't know the language, I was able to reconstruct the fragment faster than he did, because I was concentrating solely on the shapes, the color of the fibers and the flaws in the papyrus."

Déchiffrement d'un papyrus original et son édition imprimée côte-à-côte ©Sorbonne Université

Once reconstructed, the texts are translated and published in papyrology journals, accompanied by a line-by-line commentary and plates of the fragments. They can then be used by other papyrologists, historians, sociologists, anthropologists, geographers and literature specialists from all over the world to carry out more global studies on everyday life in Antiquity: taxes, accounting, livestock, the army, relationships between people, and so on. "You can have the most beautiful archaeological site in the world, but it's only going to come back to life thanks to the texts that talk about it and what people did there," asserts Benoît Laudenbach.

Much more than just a collection of ancient artifacts, Sorbonne University's cartonnage and papyri are a window into the history, cultures and languages of antiquity. And it's thanks to the ongoing work of these modern magicians at the Institut de papyrologie that ancient treasures continue to reveal their secrets.