How color became a major issue in art history

What can we learn from coloring materials about our relationship to art, fashion and decoration? What ideas and relationships with the world do our use of color convey?

The theme of color has become a classic in exhibitions. Examples for 2022 alone include "La Couleur en fugue" at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, "Bonnard. Les couleurs de la lumière" (in French) at the Musée de Grenoble and "Couleurs des Suds" at the Musée Regards de Provence in Marseille.

The success of the theme no doubt owes much to the fact that it speaks and resonates easily, in a way that we instinctively imagine as "universal". However, the perception of color is cultural and contingent, as we know from the growing number of studies since the pioneering work of John Gage in the UK (link in French) and the historian Michel Pastoureau in France.

Nevertheless, much remains to be explored in this still new field. Color as an object of study opens up multidisciplinary perspectives: what do coloring materials tell us about our relationship to art, fashion and decoration? What ideas and relationships to the world around us and to everyday objects do our use and understanding of color convey?

Color in the XIXth century

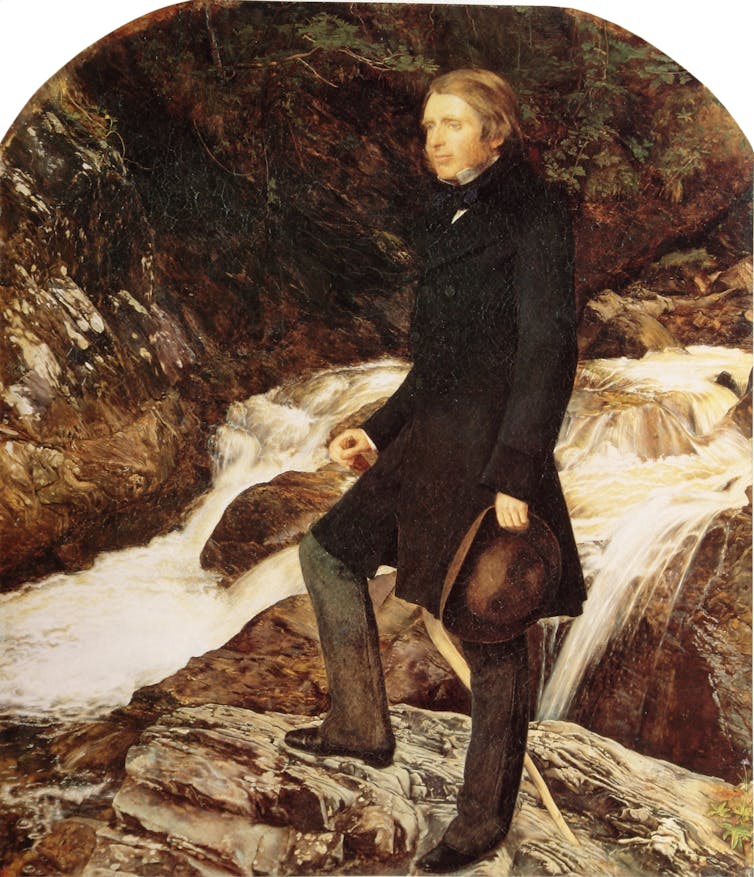

If, as Michel Pastoureau has shown, color benefits from being historicized and contextualized, few works dwell on the chromatic stakes of specific geocultural areas. This is the aim of Chromotope, an ambitious research project funded by the European Union, which explores what the 19th century did to color, and which includes my own research into the work of British writer, poet, painter and art critic John Ruskin (1919-1900). The study of a circumscribed period allows us to delve more deeply into a pivotal moment in the history of color: the second half of the 19th century, which saw the appearance of the first synthetic dyes and pigments extracted from coal tar.

It was William Henry Perkin, a young English chemist's apprentice, who first synthesized mauvéine in 1856. This accidental discovery profoundly altered the relationship to color in the arts, literature and visual culture of industrial England: mauvein, inexpensive and effective on textiles such as wool and silk, paved the way for industrial production that gave rise to a "mauve mania" in British fashion, as well as in the rest of Europe. The consequences were felt in painting, architecture and the decorative arts... but also at the heart of aesthetic debatzs of the time about the authenticity of "natural" or "artificial" colors.

Image from the exhibition: Women's day dress, England, aniline purple silk, circa 1865-70.

Manchester Art GalleryAs part of the Chromotope project, a major exhibition on color in the 19th century, "Color Revolution : Victorian Art, Fashion and Design". opens at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, on September 21, 2023. The exhibition is largely informed by the interdisciplinary work of art and literature researchers, curators and conservation scientists who have collaborated to make their research accessible to a wider audience.

The Ruskin turning point

The Victorian era in the United Kingdom, which corresponded to the reign of Queen Victoria between 1837 and 1901, was marked by the apogee of the industrial revolution and the British colonial empire, but also by a rich artistic and literary scene. Among the major figures who played a part in these transformations, John Ruskin, a highly influential art critic and great thinker on color, occupies an important place. Although less well known in France than in the UK, the work of this prolific artist, collector and writer had a particular impact on Marcel Proust, who read and translated it with great enthusiasm. This influence can be seen in many aspects of his work. In The Elements of Drawing, 1857, he wrote:

"Everything we see in the world around us presents itself to the eye only as an arrangement of spots of different colors, different shades."

In an era marked by the consolidation of a number of scientific disciplines, such as the natural and human sciences, anthropology, geology, botany and others, Ruskin stood out for his complex thinking, which eluded classification and gave pride of place to nature, morality and pedagogy. He wrote to inform his readership, teach drawing, educate young girls; he founded museum institutions for working-class populations to put beauty and craftsmanship back at the center of life and the city, such as the St George’s museum in Sheffield; he opposed industrialization, which he saw as a major danger to European civilization as well as to the natural world.

Color plays a key role in his work: it symbolizes the beauty of flora and fauna, makes painting sacred when used correctly, but can ruin an image instantly if the painter makes the slightest mistake in shades and chromatic harmonies.

In this proto-ecological relationship with the world, color is a prism through which meticulous observation of the natural environment can serve art, human beings and divine creation. Far from the chromophobic thinking of Plato, who attacked rhetoric as much as color, or his heirs, who denounced its sensual attributes, color thus becomes a sacred element for Ruskin.

Ruskin paid particular attention to the colors of nature, which he endeavored to reproduce as faithfully as possible: witness his numerous studies, particularly in watercolor, collected in the Ashmolean Museum's "Teaching Collection". This collection brings together almost one thousand five hundred works, drawn or collected by Ruskin, which served as the basis for his teaching at Oxford University from the 1870s onwards. One example is his famous kingfisher, of which there are two versions: one in black and white, the other multicolored. The bird's plumage shows the full extent of Ruskin's chromatic skill, with subtle yet brilliant touches of blue, violet, orange and all the nuances associated with texture and light. These images are available in digital format on the Teaching Collection website.

[images : Study of a Kingfisher, with dominant Reference to Colour and Study of a Kingfisher, with dominant Reference to Shade]

When he founded the museum in Saint George, on the outskirts of Sheffield, in 1857, Ruskin conceived it as a place of fluidity where fixed artistic categories had no place: what mattered to him was to revitalize art and craft. Color, which is common to all these practices, defies the temptations of classification, and in this sense serves the liberating museological impulse carried by Ruskin throughout the second half of the 19th century. It eludes the museum categories that were only just being solidified at the time. In this sense, the "Colour Revolution" exhibition is resolutely Ruskinian: it features a variety of media (drawings and paintings, as well as ceramics, stained glass, jewelry, furniture, clothing, etc.), with a cross-disciplinary approach that highlights the attention paid to the materiality of color, as well as its spiritual significance. These elements testify to the scope of Ruskin's work and influence, which extends beyond the Victorian era and influences contemporary museum practices.

Reading Ruskin, the revolution of color in the 19th century questions our relationship with nature and art, as well as the burning ethical issues of the day. We're thinking of gendered color, qualified as futile when it's vivid in women's fashion; but also of racialized color and the artistic treatment of non-white skin color in a colonialist and imperialist Europe, with its exoticizing view of Eastern colors.

All of these issues are echoed in the exhibition. Beyond the dull, gray image of Victorian England in the haze of industrialization, Ruskin offers us a range of aesthetic, artistic and political issues that resonate with our contemporary concerns.

Stella Granier, PhD. in English studies, Sorbonne University

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article in French.

![]()