24 views on Georgia, an immersive educational experience

Last Feburary, 24 aspiring journalists from Celsa, Sorbonne University’s communication and journalism school had an immersive experience in the heart of Georgia for just over a week.

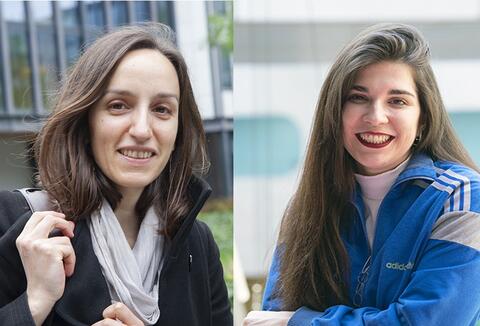

Lisa Bolz, associate professor at Gripic and project supervisor, and Nell Saignes, a student in the second year of the Master’s in journalism program, tell us about this life-size exercise in style.

Lisa Bolz: Every year, we take the Master’s in journalism class on a week-long immersion trip abroad in which we relocate our in-house editorial staff to an unknown land. The students propose three destinations to the teaching team, which decides on the basis of budgetary feasibility, journalistic interest and the security conditions in the country.

After Armenia, Kosovo, Ukraine and Senegal, this year's class spent nine days in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, accompanied by two associate journalists, a person from the Celsa audio-visual department and myself.

The aim of this experience is to give students an insight into journalistic work abroad in an unknown language. It is also an opportunity for them to put into practice the skills they have acquired throughout their studies, whether in terms of video, photography, writing, reporting or interviewing techniques.

How do you organise the work on site?

L. B.: As supervisors, we take care of all the logistics of the trip (flight, transport and accommodation). We are supported by two fixers, people on the spot who act as interpreters and help us to find contacts and addresses in the country.

The students propose topics (cultural, political, economic, educational, etc.) in agreement with the two editors. We then accompany them in writing and correcting their articles. The aim is for them to spend as much time as possible in the field reporting.

We also created a blog, called The Colchis Leaf by the class, so that they can showcase their written, video and audio production in a quick and easy way.

Nell, was your experience as a student?

Nell Saignes: For a journalism student, becoming a reporter abroad is kind of ideal. So to try it for a week is an amazing opportunity. Exhausting, but unique! The best way to get in touch with the Georgians was to do our job as journalists.

What were your days like in Georgia?

N. S.: It took us about two or three days to get our bearings. We had prepared our subjects well in advance. But once we got there, nothing ever went according to plan. We divided our time between the field and the newsroom in Tbilisi. The teaching staff was there until 9 p.m. to correct our articles and guide us.

We started every morning with an editorial conference in the hostel where we were staying, a sort of third place for start-ups and digital nomads from the diaspora of workers in creative fields, of which there are many in Georgia. Everyone worked at their own pace, but we discussed our subjects a lot and lived vicariously through the social and political life of the country, which has been disrupted by the war in Ukraine and the arrival of many Russian migrants fleeing mobilisation. Most of the reports took place in the vicinity of Tbilisi.

In one week, we each dealt with an average of two to three topics (cultural, political, sports, historical, sociological, etc.). Some of these topics had been prepared in advance, while others emerged from the discussions in Georgia.

What is your most vivid memory?

N. S.: I chose to do two stories outside Tbilisi. One involved a six-hour drive by van to find people displaced by the conflict in Abkhazia—a conflict that took place in Georgia in 1992-1993 after the fall of the USSR. After the war, many of these displaced people were relocated to sanatoriums on the outskirts of Georgia's second largest city and many still live there, but at the time I reported, the situation was changing. While the city hopes to see massive investment in new resorts to revive its tourism sector, most families have been relocated after more than 30 years in these ghostly places that still bear the scars of war.

I have fond memories of this solo adventure, although the Georgian transport system is a bit rustic and it can take a lot of logistics to get to the place of the report. And, once there, until you see your contacts, you always wonder if things will work out and whether you've come all this way for nothing. You have to send emails and call people one after the other to make sure they are there. So when all my appointments are confirmed and I can see with my own eyes the few displaced people who still live there coming to tell me their story, it was very powerful.

What difficulties have you faced in your daily life?

N. S.: There were only two fixers for the whole class. They couldn't be everywhere at once to interpret for 24 students so we often had to manage without their help during the interviews. This wasn’t easy because many Georgians do not speak English well, and as is often the case in many post-Soviet countries, people have grown up in a mainly Russian-speaking environment. I was lucky enough to speak Russian, which helped me a lot.

As a project supervisor and organiser, what feedback did you get from the students?

L. B.: Very good feedback. Most of them found the experience formative for the rest of their career. Reporting abroad is a complex and specific exercise and there is no better way to prepare for it than to experience it in real life.

Nell, where do you see your career going after this Georgian experience?

N. S.: I would love to go abroad and work in a Russian-speaking or post-Soviet region. Even if I go into television in the next few months, I may be called upon to work internationally in my career.